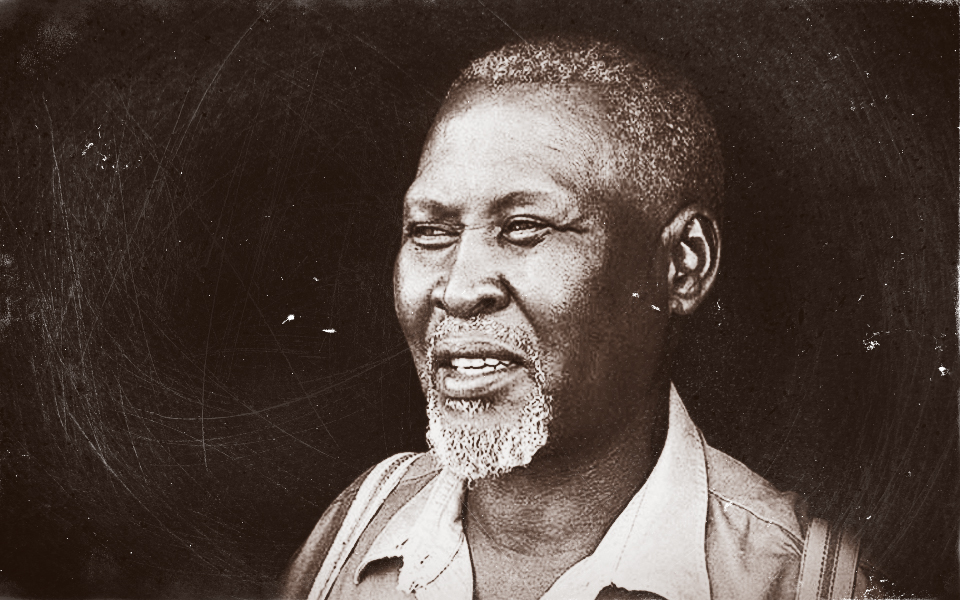

Auto biography

An Autobiographical Article, 1961

I was born of John Bunyan Luthuli of Groutville Mission Station by his wife Mtonya Luthuli, born Gumede. I was born in Southern Rhodesia at Solusia Mission Station, where my father was doing Christian missionary work as Evangelist-interpreter under the Seventh Day Adventist Church. I was born in 1898. I do not know the date of birth. My father, John Bunyan, was the second son of Ntaba Luthuli, a convert and follower of Rev. Aldin Groutville of the American Board Mission who, with three other missionaries, was sent out in 1835 by the American Board to do missionary work among the Zulus. The Rev. Groutville came south and established himself in what is now Groutville Mission Station. Officially the place is known as ”Umvoti Mission Reserve.”

My grandfather, Ntaba, was the second chief of the Groutville Community. Chieftainship in the Umvoti Mission is elective. It is not hereditary. In 1935, at the invitation of some elders of my tribe, I stood as candidate and won. Once elected you may be chief for life, unless you voluntarily resign or are deposed by the Government on its own initiative or at the request of the people. I was deposed by the Government in 1952 for participating in the Campaign for the Defiance of Unjust Laws. My predecessor was forced out because people became dissatisfied with his administration and requested the Government for an election.

I passed my Standard IV in 1914, then went to boarding schools up to Standard VI. At Edenvale Institution, a Methodist institution, I joined the Teachers’ Training Department. I graduated there as a teacher in 1917. After teaching for two years as head of a small intermediate school, I went to Adam’s College in 1920. Then I joined the staff of Amanzimtoti Institute (Adam’s College) as a teacher. I also acted as College Choir Master.

During my student days I became much interested in the work of the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Students’ Christian Association. I joined the Church when a teacher in 1918.

Fight for More Pay

I was President of the Natal African Teachers’ Union for two years. The union’s main concern was to strive for better wages and conditions of service. Eighteen pounds (sterling) per quarter and principal’s allowance was regarded as a princely salary, but it could not meet the normal needs of a man who must be exemplary in the community. Resigning from Adam’s College in 1935, I took up duties as Chief at Groutville Mission on January 1, 1936. My life as Chief followed conventional and routine duties. This involved holding courts to settle disputes and administrative work in settling family quarrels.

I interested myself in organising the African cane growers into an association. With the assistance of some elders of the tribe and younger men we formed the Groutville Bantu Cane Planters’ Association. There were then about 200 members, mostly very small growers, because land holdings were small. Because of overcrowding they now are on an average five acres each. The chieftainship introduced me directly into the vital problem of African life: their poverty, the repressive laws under which they operate.

I knew about the African National Congress as a teacher. My own senior paternal uncle, Chief Martin Luthuli, was a member. But it was only when I was chief that I became a member. I joined Congress about 1945 when Dr. Dube, the Natal President, was virtually bed-ridden through a stroke that incapacitated him until his death in 1946. In May, 1951, I stood against Mr. A. W. G. Champion for the provincial presidency. I won. The national body (A.N.C.) had in 1949 passed a programme through which the A.N.C. would pursue the freedom struggle by militant but non-violent methods. A.N.C. Leadership

It has been my privilege and arduous task to be in the leadership of the A.N.C. to help pilot it at a most testing time. I became provincial president in 1951. The first major effort was the Campaign for the Defiance of Unjust Laws in 1952. In the national election of December, 1952, I was nominated candidate. Dr. Moroka sought re-election. I won. Elections are held three-yearly. I have been re-elected on all occasions since then. I was still president-general when the A.N.C. was banned in March, 1960.

Hardly a year has passed without some demonstrations at national or provincial level. There have been national stay-at-homes. There has been a most significant political activity among African women since the Government decided in 1952 that African women, too, like their menfolk, must carry the hated pass – hated because of the suffering it causes. Since my first ban in 1953, I have virtually been under some ban to this day. My bans have been twofold: debarring me from attending gatherings and being confined to the magisterial area of Lower Tugela, Natal. The district, from my home, Groutville, has a radius of about 15 miles. Two previous bans debarred me from public gatherings. The five-year one I am serving now debars me from any gatherings, public or otherwise.

I was arrested on December 15, 1956, on a charge of treason. At the end of the lengthy preparatory examination in Johannesburg, I was committed in August, 1957, for trial with all of the others. My activities after release from the Treason Trial cost me my third ban. When this ban was a year old we were detained in 1960 from March to August under a State of Emergency. The A.N.C. added fuel to the fire by calling for a Day of Mourning for Sharpeville victims, and called upon the African people to burn their passes.

When serving my detention in Pretoria gaol with many others, I was charged with burning my pass and for inciting others. I was found guilty of burning my pass by way of demonstrating against a law. For this count I was sentenced to six months without the option of a fine, but suspended for three years, provided during this period I am not charged with a similar offence. No doubt, my ill-health made the magistrate give me a suspended sentence and an option of a fine. I am now home serving the five-year ban with the suspended sentence hanging over my head.

From Drum, Johannesburg, December 1961

Naming the Hospital

Inkosi Albert John Luthuli “Madlanduna, was a globally respected leader and spokesman for 14million oppressed, exploited and humiliated South Africans. He was a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize at the Oslo University in 1961 .In 1936 he was called by the elders of his community to come home and lead them, he then left teaching that year to become the Chief of his community. From the inception of his new calling, Inkosi Luthuli was brought face to face with ruthless African political, social and economic realities – those that denied his people any form of human or political rights, that kept them landless and prevented them from meaningful economic development. The futility and limited nature of tribal affairs and politics made him look for a higher and broader form of organisation and struggle which was national in character. It was from this background he joined the African National Congress in 1945. In 1946, he entered the then Native Representative Council, which called for the abolishment of discriminatory laws and demanded a new policies towards the African miners’ strike at Witwatersrand and towards the African population.

Inkosi Luthuli was elected Provincial President of the African National Congress in Natal in 1951. In 1952 he was deposed as a tribal Chief and elected President-General of the African National Congress by his people the same year. There were many bold and imaginative political and economic campaigns that he initiated such as those encompassed in both the 1949 Programme of Action adopted by the ANC, and in the Freedom Charter. Inkosi Luthuli was fundamentally a militant, disciplined and an uncompromising fighter who had joined and led an organisation of men and women who, like himself, fought to free the people of this country.

Through fear of his ideas and uncompromising stand for human rights, the government of the time banned and confined him to the Lower Tukela area from 1952 to 1954. But this was renewed again towards the end of 1954 for two years. He was arrested and charged with High Treason in 1956 together with other leaders of the liberation movement. The trial opened in January, 1957 and concluded on 29th March 1961 when all the accused were found not guilty. Together with 2,000 other leaders he was arrested and detained for five months in 1960 under the State of Emergency declared by the then South African Government on 29 March 1960. From then he was repeatedly banned and arrested until his death on 21st of July 1967.

Nobel Peace Prize

This year as in the years before it, mankind has paid for the maintenance of peace the price of many lives. It was in the course of his activities in the interests of peace that the late Dag Hammarskjold lost his life.

Of his work a great deal has been said and written, but I wish to take this opportunity to say how much I regret that he is not with us to receive acknowledgement of the service he has rendered to mankind. It is significant that it was in Africa, my home continent, that he gave his life. How many times his decisions helped to avert world catastrophes will never be known, but there can be no doubt that he steered the United Nations through some of the most difficult phases in its history. His absence from our midst today should be an enduring lesson for all peace-lovers and a challenge to the nations of the world to eliminate those conditions in Africa which brought about the tragic and untimely end to his life.

As you may have heard, when the South African Minister of the Interior announced that subject to a number of rather unusual conditions, I would be permitted to come to Oslo for this occasion, he expressed the view that I did not deserve the Nobel Peace Prize for 1960. Such is the magic of the Peace Prize that it has even managed to produce an issue on which I agree with the Government of South Africa, although on different premises. It is the greatest honour in the life of any man to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and no one who appreciates its profound significance can escape a feeling of inadequacy when selected to receive it. In this instance, the feeling is the deeper, not only because the selections are made by a committee of the most eminent citizens of this country, but also because I find it hard to believe that in this distressed and heavy-laden world, I could be counted among those whose efforts have amounted to a noticeable contribution to the welfare of mankind.

I recognise, however, that in my country, South Africa, the spirit of peace is subject to some of the severest tensions known to man. For that reason South Africa has been and continues to be in the focus of world attention. I therefore regard this award as a recognition of the sacrifices by my people of all races, particularly the African people, who have endured and suffered so much for so long. It can only be on behalf of the people of South Africa, especially the freedom-loving people, that I accept this award. I accept it also as an honour, not only to South Africa, but to the whole continent of Africa, to all its people, whatever their race, colour or creed. It is an honour to the peace-loving people of the entire world, and an encouragement to us all to redouble our efforts in the struggle for peace and friendship.

For my own part, I am deeply conscious of the added responsibility which the award entails. I have the feeling that I have been made answerable for the future of the people of South Africa, for if there is no peace for the majority of them, there is no peace for any.I can only pray that the Almighty will give me strength to make my humble contribution to the peaceful solution of South Africa`s and indeed the world`s problems. Happily I am but one among millions who have dedicated their lives to the service of mankind, who have given in time, property and life to ensure that all men shall live in peace and happiness. It is appropriate at this point to mention the late Alfred Nobel, to whom we owe our presence here, and who, by establishing the Nobel Institute, placed responsibility for the maintenance of peace on the individual, so making peace, no less than war, the concern of every man and woman on earth – whether they be in Stanger or Berlin, in Washington or the shanty towns of South Africa.

It is this catholic quality in the late Nobel`s ideals which has won for the Nobel Peace Prize the importance and universal recognition which it enjoys. In an age when the outbreak of war would wipe out the entire face of the earth, the ideals of Nobel should not merely be accepted or even admired: they should be lived. Scientific inventions at all conceivable levels should enrich human life, not threaten its existence. Science should be the greatest ally, not the worst enemy, of mankind. Only so can the world not only respond to the worthy efforts of Nobel, but also insure itself against self-destruction.

In Africa, as our contribution to peace, we are resolved to end such evils as oppression, white supremacy and racial discrimination, all of which are incompatible with world peace and security. We are encouraged to know, by the very nature of the award made for 1960, that in our efforts, we are serving our fellow men the world over. May the day come soon, when the peoples of the world will rouse themselves, and together effectively stamp out any threat to peace, in whatever quarter of the world it may be found. When that day comes, there shall be peace on earth and goodwill between men.